Key points

- One of most unassuming pieces of Japanese language (っす-ssu) can carry multiple and important meanings

- In written online metadiscourses, these complex and varied meanings are reduced to a limited and stereotypical set

- The way people use the -su style in everyday conversations and the way they talk about how they use it/how they think it should be used differ considerably

内容紹介

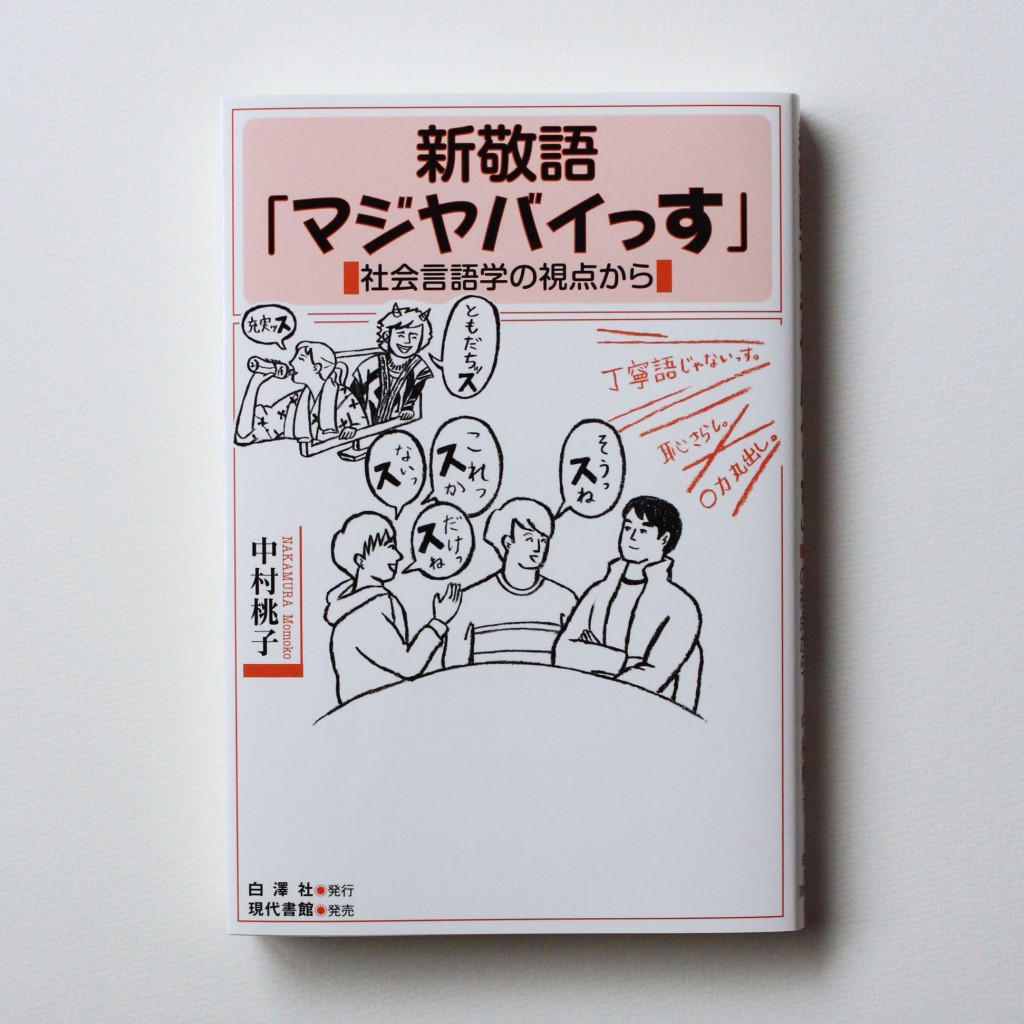

「そうっすね」「マジっすか」など、体育会系の若者ことばと言われる「っす」言葉。男子大学生たちの会話、ウェブサイトの書き込み、テレビCMでの「っす」言葉の使われ方を分析し、単なる若者言葉だとみなされている「っす」言葉が実にさまざまな表現を担っていることを社会言語学の視点から明らかにする、初の「っす」言葉研究書を読んでみました。とても勉強になったので、本稿では中村桃子著「新敬語―マジヤバイっす」を読んだ感想を述べていきます。

What the book is about

I’ve just finished reading 新敬語「マジヤバイっす」 shinkeigo maji yabai-ssu ‘new honorifics maji yabai-ssu’ (which can be roughly translated as ‘it’s insane’), by Nakamura Momoko, published in 2020 by Hakutakusha.

You can find the book here

The book explores the meanings and functions ofっす –ssu (henceforth –su), the shortened version of the copula desu. Oversimplifying things, the copula desu (and the verbal suffix -masu) are usually referred to as “polite” because they index either interpersonal distance between the participants and/or the producer’s heightened awareness of the receiver, hence are commonly used in situations where there is some kind of hierarchical relationships (上下関係) between interactants. For instance, you would use the desu/masu style in the workplace, with a senpai or with someone you are meeting for the first time. Using a different, more informal style can, depending on the situation, have the same derogative effects as a swear word in English. Similarly to desu, -su is also used to display the speaker’s acknowledgement of the hearer’s different status, age, or power in the relationship. Despite these important meanings, it is usually associated with Japanese slang used by young men and is quickly dismissed as “incorrect” use.

In her book, Nakamura investigates the -su style as observed in three different settings: (a) informal conversations among both male and female university students, (b) written online communication (the web forum Hatsugen Komachi) and (c) TV commercials. By the way, the commercial I enjoyed the most is the one with 鬼ちゃん ‘demon chan’, played by Suda Masaki:

Indexicality and gendered identities

Going back to the study, it convincingly demonstrates that -su is (surprise!) a multifunctional and highly contextual style that indexes different meanings depending on the situation where it is used, the people involved and their interactional goals. It’s a highly complex interactional device that successfully responds to two apparently conflicting social needs: reducing social distance whilst conveying deference. If the context allows it, the -su style can also be used to (not necessarily self-consciously) challenge the ideological constructs of “male” versus “female” identities. When used by men, it can index a “lightheartedness” (via what Nakamura calls the 軽いス体 ‘light -su style’ exemplified, e.g., by how demon chan talks in the above CM) that contrasts with the Japanese model of hegemonic masculinity embodied by the sararīman ‘salaried man’, an employee with total devotion to the workplace. Conversely, when used by women, it can signal an emergent feminine identity that is not shaped (or at least not as much as it used to be) by the male gaze.

Metadiscourse

Interestingly enough, although quite unsurprisingly, these and other complex interactional meanings that emerge in spontaneous conversation and TV commercials are drastically reduced in the mediatised website discourse of Hatsugen Komachi, where the -su style is framed as “incorrect”, humorous and generally inferior to the desu/masu style. This type of metadiscourse (that is, a piece of language used to comment on language and language use) reveals the considerable ideological effort required to maintain the language use (and the social identities it indexes) perceived as “correct”, “natural” and “legitimate”.

In sum

I truly enjoyed this book because it reveals how much we can learn from one of the shortest and most unassuming pieces of the Japanese language – su. Moreover, it introduces many theoretical concepts (indexical field, indexical regimentation, stylistic/stylised crossing, language ideology and intertextuality, to just name a few) in a comprehensible and truly accessible way, yet without oversimplifying things. Last but not least, it’s fun to read! The book is in Japanese, but part of it is taken from this article in English:

Nakamura, M. (2021). Linguistic impoliteness in a polite society: Ideology and practice in Japanese spoken and written discourse Introduction. East Asian Pragmatics, 6(1). https://doi.org/10.1558/eap.18181

Thank you for reading till the end and あざっすー 🙇🏼♀️

Leave a comment