Photo by Wang Xi on Unsplash

Access the original article here – it is longer but makes more sense!

Key findings

- What constitutes ‘apologies’ and ‘thanks’ across languages does not necessarily match what we mean by apologies and thanks in English

- For our findings to be sound we need to contextualise and problematise the English scientific labels we use

- In Japanese the distinction between ‘apologies’ and ‘thanks’ is more opaque than it is commonly taken to be

- The notion of pragmatic space is a timely addition to the toolkit of linguists: it allows us to visualise areas of overlap as well as differences between apparently similar acts

言語比較の問題点

言語を比較するのは、ある言葉・表現が二つ以上の言語にどのように使用されているか、どの意味を持っているか、などを分析するということである。例えば、英語のapologyと日本語の「謝罪」を比較すると、英語の apology は gratitude と違う意味を持っているが、日本語の「謝罪」は「感謝」という意味も含まれている。証拠として、「すみません」は謝罪も感謝の気持ちも伝わるが、sorry はそうでもない。

これは当然のことと思われるかもしれないが、西欧の文化の影響が大きい言語学にはついつい最近までは英語に当てはめるものが一般化されてしまった。つまり、apology と「謝罪」のように、辞書的に対応している言葉であるため、全く同じ機能・意味があると思われていたが、そうとは限らない。なぜならば、言葉は社会や文化の中で発展しているものなので、その社会・文化に大きく影響されているからである。これは言語学にも当てはまる。例えば、学術・学位論文を英語で書いても、英語も英語社会・英語文化と関わりがあることに間違いない。その結果、当たり前のように日本語を英語で説明しようとすると、誤解が起こる可能性を孕んでいる。

以上を踏まえて、英語以外の言語を英語で記述する時は、注意すべきである。もちろん、英語と日本語、または欧米社会と日本社会は全く違うわけではなく、英語以外の言語を英語で記述できないわけでもないが、少なくともどの言語でもその社会・文化と密接に関わっていることを認識すべきである。

Do Japanese people apologise all the time?

We often hear that “Japanese people apologise all the time”. But what if they simply use words that, in their English translations, are conventionally associated with apologies, with meanings other than being sorry?

Speech acts across languages

In the field of linguistics I specialise in, we are kind of obsessed with “speech acts”, that is, expressions such as apologies, requests, promises, etc. by which we do something. For instance, by saying “It’s hot in here” (and I can assure you that right now in Italy is unbearably hot, thank you heatwave), I may simply describe the current situation (possible, but unlikely), or I could imply that I want you to open the window – in other words, making a request. Many scholars have looked at a variety of speech acts, with a variety of methods. Nonetheless, the labels we use to identify such speech acts are very rarely problematised. In what follows, I will try to show that the words ‘apology’ and ‘thanks’ may acquire different meanings in different contexts, and even more so when we talk about ‘apologies’ and ‘thanks’ in a language such as Japanese, which is typologically quite different from English.

Sumimasen

The expression I selected to corroborate or otherwise the assumption that ‘apologies’ in English may be different from ‘apologies’ in Japanese is すみません sumimasen, which is typically associated with the expression of regret and commonly translated in English with ‘(I’m) sorry’. First, I looked at sumimasen in texts collected from the Japanese Q&A website Yahoo! Chiebukuro, an online forum where people talk at length about many things, including language use. What I found was that Japanese speakers frame sumimasen as an expression of both apology and gratitude:

- Kansha no imi o arawasu ‘sumimasen’ wa, ‘nani no okaeshi mo dekizu sumimasen’ no imi kara ka, ‘kokoro ga sumikiranai’ no imi kara hanare, shazai o arawasu yō ni natte kara no hyōgen desu.

‘The “sumimasen” that expresses gratitude [kansha] takes the distance from “sumimasen for not being able to give you anything in return”, or the idea that “my heart is not at peace”, and it has developed after expressions of apology [shazai]’

This example attests to the ambivalent nature of sumimasen, supporting the assumption that Japanese speakers conceptualise ‘apologies’ as closely associated with ‘thanks’. What also struck me is that here the speaker use specific terms to denote ‘apologies’ (shazai and o-wabi), while the equivalent of ‘thanks’ is kansha, which literally means ‘gratitude’. In other words: in Japanese there seems to be no direct counterpart of ‘thanks’, which is indirectly verbalised through the feeling it evokes.

But what if these are nothing more than the very subjective opinions of two individual speakers? To find out whether they reflect how Japanese people in general (or at least a sample larger than two people) think of ‘apologies’ and ‘thanks’, I looked sumimasen up in the web corpus (i.e., a large collection of texts in electronic format) JaTenTen11 (https://www.sketchengine.eu/) which is huge (10 million words!), hence much more reliable. What I found is a number of examples supporting the assumption that in Japanese the distinction between ‘apologies’ and ‘thanks’ is indeed more opaque than it is commonly taken to be:

- O-isogashii jikan o saite shirabete sumimasen deshita.

‘*Sorry/thank you for sparing your precious time and looking [it] up for me. Thank you [arigatō gozaimasu].’

In this example, expressions of ‘apologies’ (sumimasen) and ‘thanks’ (arigatō gozaimasu) co-occur, further corroborating the assumption that the two speech acts are indeed related. This is also testified by the pervasive use of benefactive verbs (a fancy word to indicate verbs which are used, among other things, to stress that someone did something for us) immediately at the left of sumimasen, as in

- Iroiro ki o tsukatte morai sumimasen ^^

‘Sorry/thank you for your consideration (kaomoji)’

Pragmatic space

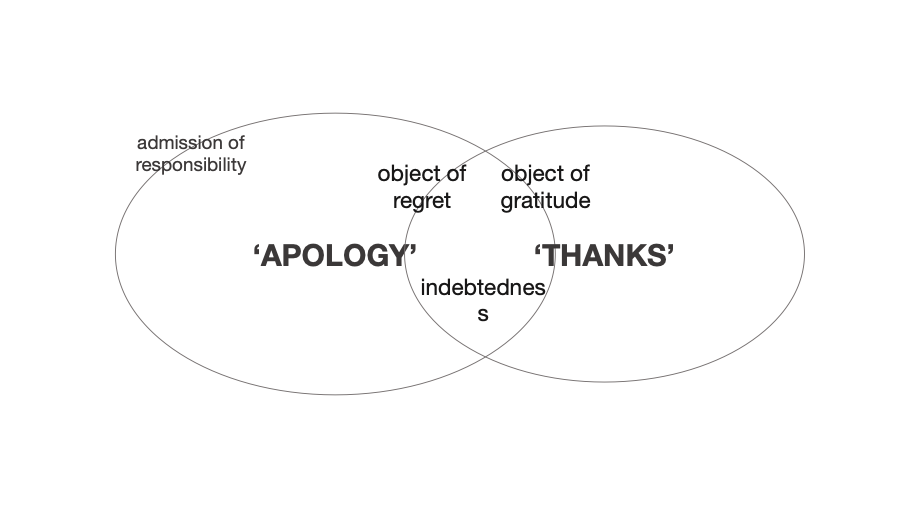

When someone does something for our benefit, in Japanese we can ‘thank’ them with the equivalent of the English word sorry. I tried to illustrate this overlapping of ‘apologies’ and ‘thanks’ in Japanese in terms of pragmatic spaces: conceptual spaces where we can locate meanings and functions of specific speech acts, and that can then be used for cross-linguistic comparison.

The figure tentatively shows that, in a nutshell, in Japanese there is no clear-cut distinction between what we feel regret for and what we feel grateful for – sumimasen can convey both.

Conversely, there is no standardised English construction that can convey both ‘apologies’ and ‘thanks’, and the two pragmatic spaces overlap to a less degree.

In sum

We can thus safely conclude that apologies and thanks in English do not perfectly match what shazai and kansha index in Japanese. Overlooking this distinction may hinder meaningful cross-linguistic comparison.

A final reminder that if you’re interested in finding out more about this research, you can have a look at this article (OA)🏄🏼♀️

Selected references

Austin, John L. 1964. How to do things with words. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Brown, Penelope and Levinson Stephen C. 1987[1978]. Politeness. Some universals in language usage. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Coulmas, Florian. (ed.). 1981. Conversational routine: Explorations in standardized communication situations and prepatterned speech. Berlin: De Gruyter Mouton.

Culpeper, Jonathan and Tantucci Vittorio. 2021. The Principle of (Im)politeness Reciprocity, Journal of Pragmatics. 146–164.

Goddard, Cliff & Wierzbicka Anna. 2013. Words and Meanings: Lexical Semantics Across Domains, Languages, and Cultures. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Hasegawa, Yoko. 2018. Benefactives. In Hasegawa, Yoko (ed.), The Cambridge Handbook of Japanese Linguistics. 509–529. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Ide, Risako. 1998. ‘Sorry for your kindness’: Japanese interactional ritual in public discourse. Journal of Pragmatics 29(5). 509–529. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0378-2166(98)80006-4.

Jucker, Andreas. H. & Taavitsainen Irma. 2008. Speech acts in the history of English. John Benjamins: Amsterdam; Philadelphia.

Minsky, Marvin. 1977. Frame-system theory. In Johnson-Laird, P. & Wason, Peter C. (eds.), Thinking. Readings in Cognitive Science. 355–376. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Miyake, Kazuko 三宅和子. 1993. Kansha no imi de tsukawareru wabi hyōgen no sentaku mekanizumu. Coulmas (1981) no indebtedness ‘kari’ no gainenn kara no shakai gengo gaku teki tenkai 感謝の意味で使われる詫び表現の選択メカニズムーCoulmas(1981)のindebtedness「借り」の概念からの社会言語学的展開- (The mechanisms of selection of apologetic expressions used to express gratitude: A sociolinguistic study on Coulmas’ (1981) notion of ‘indebtedness’). Tsukuba daigaku ryūgakusei ronshū 8. 19–38.

Ohashi, Jun. 2010. Linguistic rituals for thanking in Japanese: Balancing obligations. Journal of Pragmatics 40. 2150–2174.

Searle, John. 1969. Speech acts: an essay in the philosophy of language. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Wierzbicka, Anna. 1996. Japanese Cultural Scripts: Cultural Psychology and “Cultural Grammar”. Ethos 24(3). 527–555.

Leave a comment